This week, as promised, I take a short break from book news to share with you a recent article about Julius Rosenwald and efforts to turn his great project of small primary schools for rural African Americans across the South, into a National Historical Park:

Julius Rosenwald with students from a Rosenwald school. Courtesy of Fisk University, John Hope and Aurelia F. Franklin Library, Special Collections.

An effort is underway to honor the Rosenwald schools, created by a son of German Jews to serve rural Black communities.

A coalition of Blacks, Jews and others are lobbying for a new national park to honor the Rosenwald schools, which were founded by a son of German Jewish immigrants to serve rural Black communities in the Jim Crow era.

Julius Rosenwald. Photo by Bain News Service/Buyenlarge/Getty Images.

Julius Rosenwald made a fortune investing in the Chicago-based Sears, Roebuck and Co. He ultimately bought out the company’s founders and turned the famed catalog business into a retail behemoth not unlike today’s Amazon.

Rosenwald was inspired to create the schools after reading Booker T. Washington’s 1901 autobiography, “Up from Slavery,” and meeting with him. The schools are viewed as one of the most ambitious examples of Black-Jewish cooperation in U.S. history.

More than 5,000 Rosenwald schools were built in rural areas in 15 Southern and border states between 1912 and 1932. The schools’ many distinguished alumni include the late civil rights activist U.S. Rep. John Lewis and poet-novelist Maya Angelou.

The campaign for the Julius Rosenwald & Rosenwald Schools National Historical Park is led by Dorothy Canter, a retired biophysicist who worked for the federal government for 29 years. Canter is Jewish, but had never heard of Rosenwald until she saw Aviva Kempner’s 2015 documentary, “Rosenwald.”

The park proposal

A self-described “National Parks junkie,” Canter realized that “not one of the more than 400 parks told the story of a Jewish American. Not one gave an historical perspective into the Jewish values Rosenwald embodied that brought hope and change to so many African American communities and lives.”

In 2018, Canter and other like-minded activists gathered to establish the Rosenwald Park Campaign. They courted a diverse group of religious and civic groups — many predominantly Black or Jewish — to support the project. Congress in 2020 authorized a study, which is underway.

It’s not easy to establish a new national park — only Congress can bestow the designation and the National Park Service’s criteria are exacting. But the Rosenwald campaign appears to be on the fast track. It has the support of the park system’s National Register for Historic Preservation, and a month-long period for public comment ended in July.

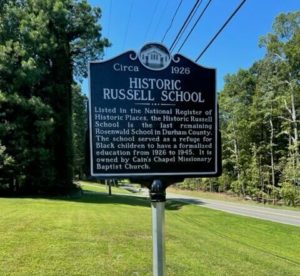

As envisioned by its backers, the park would include a visitors center in Chicago and five representative schools around the country. Ten of the 500 Rosenwald schools still standing are under consideration as park sites, including the Russell Rosenwald School outside Durham, North Carolina.

The Russell School

The Russell Rosenwald School. Courtesy of Phyllis Mack Horton.

The Russell School is the last Rosenwald school in Durham County out of an original 17. The school closed in 1945 but was preserved by the Cain Creek Missionary Baptist Church next door, which used it as a social hall for years. Today, at least as many Russell School alumni are buried in the cemetery between the church and school as are still alive.

“This is my legacy,” said Phyllis Mack Horton, director of the nonprofit Friends of Russell Rosenwald School, her pride palpable as she pointed out the flooring, chalkboard and lone student’s desk on an informal tour. The two-room, century-old wooden structure is illuminated by natural light from floor-to-ceiling windows, a hallmark of the Rosenwald design, though electric lights were later added.

Rosenwald and Washington met in 1911. Washington wanted to build small schools in African American

A marker at the Russell Rosenwald School in North Carolina. Photo by Mark I. Pinsky.

communities across the South, each staffed with two to four teachers. Initially, Rosenwald funded the schools himself. Beginning in 1917, a philanthropy he created, the Rosenwald Fund, provided between a fifth and a third of the money for each school. Another third came from local communities contributing land, labor, materials or cash. The final third came from local and state governments, which saw the project as a way to keep African Americans — a cheap local labor force — from joining the Great Migration out of the South.

The schools were state of the art, designed by a team of Black architects led by Robert R. Taylor, MIT’s first Black graduate and the first accredited African American architect. By 1928, Rosenwald schools served a third of Black children in the rural South.

Don’t miss the rest of the article! Click here to read more.

Follow me on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram to learn more. The quickest way to reach me is by email: osopinsky@gmail.com.